Meet Arunachalam Muruganantham, an award-winning social entrepreneur from Coimbatore, India, better known as the nation’s ‘Menstruation Man’. Deeply disturbed by the unhygienic menstruation practices among women in rural India, Muruganantham took it upon himself to find a solution to the problem. After several years of hard work, he invented a machine that women can use to produce their own sanitary napkins, at less than a third of the cost of commercial ones.

Born in 1962 to handloom weavers in Coimbatore, Muruganantham was forced to drop out of school at age 14 to provide for his family after his father’s death. For years he lived in poverty, working a number of jobs – machine tool operator, farm laborer, welder, and sales agent – just to make ends meet. But things were about to change soon after his marriage to a woman named Shanthi, in 1998. He discovered that his wife used filthy rags during her menstrual cycle because they couldn’t afford to buy sanitary pads, and this troubled him greatly.

Photo: YouTube video caption

“All this happened in my early marriage days,” he said, speaking to Al Jazeera. “To impress my new wife, what I would do is offer her small small gifts. On a particular day I saw a very nasty rag cloth with a few blood stains here and there on the cloth. Then I understand she’s adopting unhygienic methods to manage her period days.” So he decided that he would make DIY napkins for her to use instead of rags.

Muruganantham’s first experimental pads were made of cotton; he bought a roll of cotton wool, cut it into rectangular strips about the same size as a commercial napkin, and wrapped each strip in a thin layer of cotton cloth. Sadly, his wife rejected these pads and told him they were useless. “I got a feedback that that was very bad,” he said. “She told me ‘I’m going back to my rag cloth method.’” But Muruganantham wasn’t ready to give up – the failure of his first prototype spurred him to keep trying different materials and techniques.

Over the course of his trials, Muruganantham faced a new challenge – he had to wait an entire month for his wife to try out each prototype, and that was slowing down the process. So he approached a few female medical students at a university nearby and handed them free samples of his inventions. But mensturation isn’t an openly discussed subject in India, and the women were too shy to talk to him about their experience. That’s when he made a rather unusual decision – to test the napkins on himself.

Photo: Jayashree Industries

To do this, Muruganantham built a fake uterus with a rubber bladder and tube, and filled it with animal blood. He wrapped the contraption around his hip and had the tube drip blood into his underpants every time the bladder was pressed. This new arrangement allowed him to test several prototype napkins, but there was a major downside – he began to reek of blood and his pants were always stained. His neighbours thought he was a crazy pervert, and his wife, unable to tolerate their taunts, left him to go live with her mother.

“She never came back,” he said. “On the 20th day, I got a divorce notice. That’s the first accolade I got for my research.”

The shock of the separation didn’t discourage Muruganantham – he was still determined to complete what he set out to do. In fact, his mission had grown in proportion. Although he started out just wanting to help his wife, he found out along the way that only 10 to 20 percent of Indian women have access to hygienic menstrual products. And he wanted to help them all.

Photo: YouTube video caption

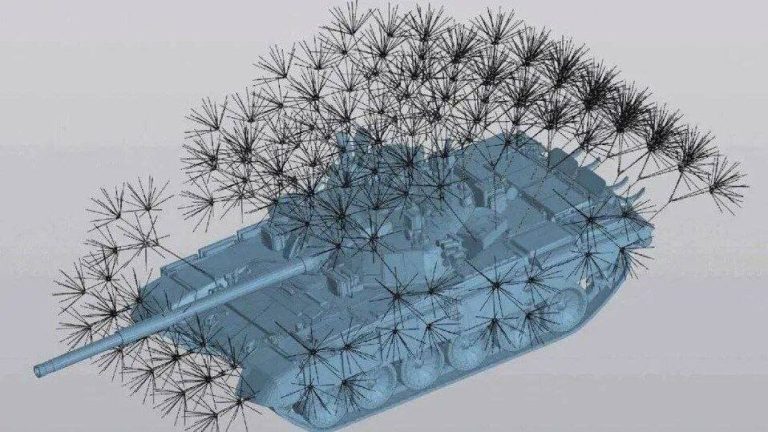

Two years later, Muruganantham finally made a breakthrough – he realised that commercial manufacturers use cellulose fibers derived from pine bark wood pulp to make their pads. He discovered that these fibers absorb a lot of fluid while retaining their shape, and also that the imported machines required to make such pads cost a whopping $500,000. So he set himself a new goal – to invent a machine that would produce napkins at a fraction of the cost.

Four years later, he managed to invent an easy-to-use machine that could grind, de-fibrate, press, and sterilize napkins under UV rays. “I made three machines, what the big, million-dollar plants are making,” he explained. “Now any uneducated woman can make world class sanitary pads.”

Next, Muruganantham raised funds to set up ‘Jayaashree Industries’, a company that sells these $950 machines to several female self-help groups (SHGs) across rural India. 1,300 such machines have been sold so far to women in 27 of India’s 29 states, to produce their own napkins and sell the surplus. This has generated employment for women – 877 local brands are currently making pads using Muruganantham’s machine. The machines are also being exported to 17 other developing countries in the world, but he refuses to sell them to large corporations.

For his phenomenal work and dedication, Muruganantham has received several accolades, including the Padma Shri, India’s fourth highest civilian award. A prize-winning documentary film was made on his story in 2013, titled Menstrual Man. And in 2014, TIME magazine featured him among the 100 Most Influential People in the World. But perhaps the best prize of all was that his wife, hearing of his achievements, decided to to go live with him again.

“I saw him speaking on TV,” she said, “and articles about him in magazines. I found his phone number in a magazine and called him a few times. He called and we spoke after five years. Then we got back together.” A happy end to an amazing story.

Sources: Al Jazeera, BBC, TIME Magazine