Epicenter, a technology startup hub in Stockholm, Sweden, has been offering employees the chance to have a small microchip implanted in their hand, ever since 2015. So far, 150 of its 3,000-strong staff have taken bosses up on their offer, and they couldn’t be happier with their decision.

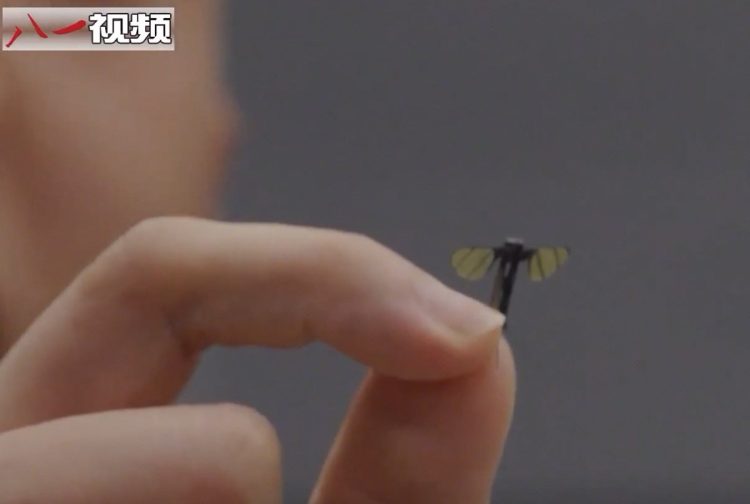

Implantable microchips the size of a grain of rice have been around for a while now, but they are usually used as virtual identification plates for pets, or as tracking devices for deliveries. Up until a couple of years ago, when Epicenter started offering its employees the chance to have them implanted into their hands, these tiny devices had never been used to tag humans on a large scale. For many people, having a chip inserted into their body sounds like something out of a dystopian future, or, at the very least, raises privacy questions, but the 150 Epicenter employees who have had them implanted say the technology just makes their life easier.

Photo via Pinterest

Instead of tracking their whereabouts at all times, collecting information about how much they work, or any sinister monitoring data of any kind, these implants are simply designed to help employees get around the workplace easier. No more having to keep an access card on them to open doors, operate company printers or order lunch at the cafeteria. With the chip, all they have to do is wave their hand in front of the scanner and magic happens.

“The biggest benefit I think is convenience,” Epicenter co-founder and CEO, Patrick Mesterton, told the Associated Press. “It basically replaces a lot of things you have, other communication devices, whether it be credit cards or keys.”

Photo: Biohax/Facebook

The microchip implantation has become sort of a tradition at Epicenter, ever since Mesterton himself had his inserted in his hand, two years ago. The company offers this option to its employees, for free, and holds parties whenever someone decides that they want to become a rudimentary cyborg.

The procedure is quick and relatively painless. Jowan Osterlund, a self-described ‘body-hacker’ from Biohax Sweden, visits Epicenter whenever a new employee want to join the cyborg club, and injects the tiny chip into the flesh right next to the thumb. It apparently feels like a quick injection and there’s hardly ever any blood involved.

Photo: Biohax/Facebook

“We already interact with technology all the time,” Epicenter employee Hannes Sjoblad told the BBC, in 2015. “Today it’s a bit messy – we need pin codes and passwords. Wouldn’t it be easy to just touch with your hand? That’s really intuitive.”

“We want to be able to understand this technology before big corporates and big government come to us and say everyone should get chipped – the tax authority chip, the Google or Facebook chip,” Hannes added, convinced that this way he will be able to question the way the technology is implemented from a position of much greater knowledge.

Photo: Biohax/Facebook

For some Epicenter employees, getting implanted is all about convenience, others just think it’s a cool way to experience the future before it happens, and some don’t even want to hear about it. Asked if he was considering getting implanted, one young man said “absolutely not”.

The microchips may be popular at Epicenter, but not everyone is thrilled about this practice. Ben Libberton, a microbiologist at Stockholm’s Karolinska Institute, said that it’s a question of how advanced the microchips will become.

“The data that you could possibly get from a chip that is embedded in your body is a lot different from the data that you can get from a smartphone,” he told AP. “Conceptually you could get data about your health, you could get data about your whereabouts, how often you’re working, how long you’re working, if you’re taking toilet breaks and things like that.”

For now, the chips used by Epicenter are based Near Field Communication (NFC) technology, the same type used in contactless cards. They are passive, meaning they contain information that other devices can read, but cannot read information themselves.