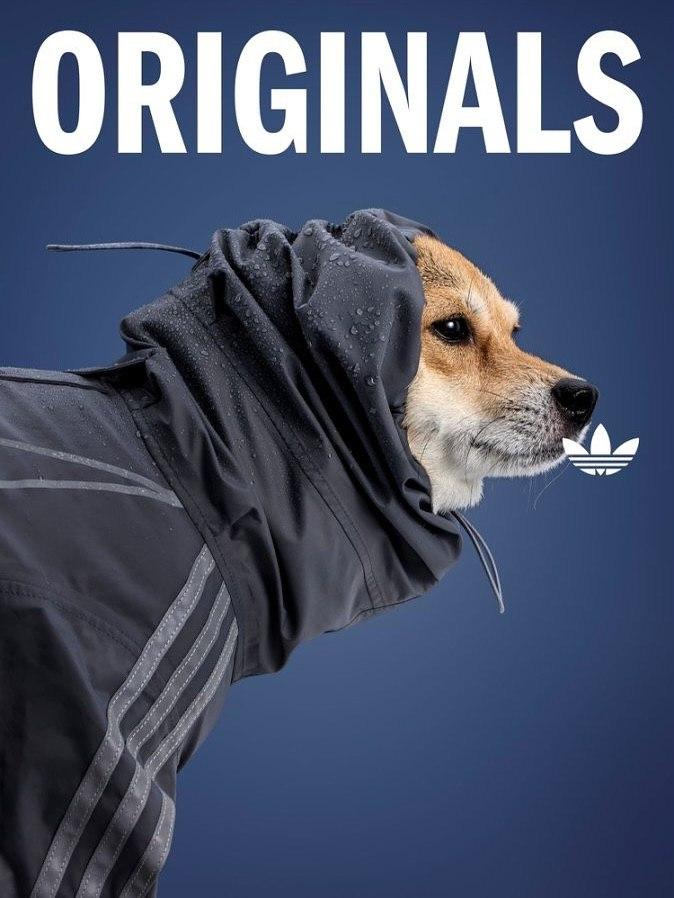

The Lyall’s wren was a species of small, flightless birds that once thrived on Stephens Island, in New Zealand. It’s one of the many species that have been rendered extinct by the reckless introduction of predators in their natural habitat, but what makes this bird’s story unique is that it was allegedly both discovered and wiped out by a house cat named Tibbles.

The lighthouse on Stephens Island was built in 1892, but the existence of a yet-undiscovered species of bird on this small patch of land was only reported a couple of years later, when assistant lighthouse keeper David Lyall moved in, along with a small staff and his pregnant cat, Tibbles. Lyall was a passionate naturalist and amateur ornithologist, and was looking forward to pursuing his hobbies on this previously uninhabited island, but little did he know that he would go down in history as the man who discovered the Lyall’s wren and indirectly caused its extinction, both in less than a year.

Photo: bogitw/Pixabay

According to All About Birds, Lyall’s pet, Tibbles, was the first cat to set foot on Stephens Island. In fact, before her arrival, in 1894, there had never been any mammalian predators on the island. Once there, all she had to do was follow her predatory instincts to cause havoc among the local bird population, including a particularly rare species now known as Lyall’s wren. No one knows how Tibbles was like as a pet, but if she was anything like most cats, she probably loved roaming the island in search of prey, and the story goes that she quickly started bringing David Lyall some of her catches, including whole, or partially eaten specimens of a small bird he didn’t recognize.

The Lyall’s wren has been extinct for over a century, but records describe it as a flightless bird small enough to fit in the palm of a person’s hand, featuring an olive-brown plumage with a distinctive yellow stripe through the eye. Its chest lacked a keel to anchor the muscles necessary for flight, and its wings were small and rounded, with loose feathers that weren’t airtight enough for flight. David Lyall described it as an almost nocturnal bird “running around the rocks like a mouse and so quick in its movements that he could not get near enough to hit it with a stick or stone”. Unfortunately, it wasn’t fast enough to escape his cat.

When the assistant lighthouse keeper examined some of the birds Tibbles had brought him as trophies, he found that he didn’t recognize the species. After writing to several ornithologists in New Zealand, describing this mysterious bird, he learned that they couldn’t identify it either. He managed to preserve over a dozen wrens, by taking out their insides and letting them dry in the sun, and sent them to prominent ornithologists like Walter Rothschild, Walter Buller, and H. H. Travers.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain)

Experts started writing about this new species of bird discovered on Stephens Island in journals, and one reportedly paid a small fortune for a few of the preserved specimens. Many of them suggested that the new species be named Traversia lyalli, in honor of David Lyall, the man who had first spotted the birds, and H.H. Travers, the ornithologist who helped him spread awareness about them.

But while experts were writing about the Lyall’s wren and deciding on the species’ scientific name, Tibbles the cat continued hunting the poor flightless birds, whose speed couldn’t save them from her sharp claws and teeth. To make matters worse, the cat, who was pregnant when she arrived on Stephens Island, had a litter of kittens, who started reproducing as soon as they became old enough to do so.

If an unrelated mate is not available, cat siblings will eventually mate with each other and even with the mother. Female cats can produce litters of up to eight kittens, and can be impregnated again just a few days after giving birth. Cats tend to breed rapidly and often, so it’s not that unsurprising that in just a few months’ time, the Lyall’s wren went from having to survive one efficient predator, to dealing with dozens of them.

Photo: LawrielM/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Before David Lyall even realized the danger Tibbles and her brood posed to the flightless bird he had discovered, the Lyall’s wren was almost completely wiped out. In a letter he sent to the mainland in February of 1895, the lighthouse keeper wrote “…the cats have become wild and are making sad havoc among the birds…”. By the time the letter was sent out, there had been just two sightings of live birds, the other being corpses brought by Tibbles.

A month after Lyall expressed his fears in his letter, an editorial in Christchurch newspaper The Press confirmed ornithologists’ biggest fear: “there is very good reason to believe that the bird is no longer to be found on the island, and, as it is not known to exist anywhere else, it has apparently become quite extinct. This is probably a record performance in the way of extermination.”

Of all the Lyall’s wrens that once thrived on Stephens Island, only the 15 specimens once preserved by David Lyall himself remain, exhibited at nine different museums around the world. They act as sad reminders of the devastating effects that the introduction of a single invasive predator in a species’ ecosystem can have.

Photo: Avenue/Wikimedia Commons (GNU Free Documentation License)

As for the cats of Stephens Island, they continued to reproduce and feast on whatever prey was available for years. In 1899, a new lighthouse keeper was installed on the island and he reportedly shot and killed over 100 feral cats in the first nine months there. However, Stephens Island only became completely cat-free in 1925.