Darshan Karwat, a post-doctorate at the University of Michigan, is making headlines for having maintained an incredibly frugal and sustainable lifestyle during his student years. The man gave up fast food, new clothes, and even toilet paper, until he got to a point where his trash for an entire year fit in just two plastic bags!

Karwat, who is originally from India, started the trash-free experiment when he lived in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and managed to keep it going for two and a half years. In the first year, he produced only 7.5 lbs of trash, and in the second year, he brought that number down to a meager 6 lbs, which is a mind-blowing 0.4 percent of the 1,500 lbs of yearly trash produced by the average American.

Looking back, Karwat says that his inspiration to start the project came from an episode of the radio show The Story, on which he heard of a British couple who lived trash-free. “I walked home from my laboratory at the University of Michigan and told my roommate Tim that I thought I could do better – I’d live trash- and recycling-free and that I’d start soon,” Karwat wrote in an essay for The Washington Post. “And just like that, I began an experiment in individual activism in the face of large environmental problems.”

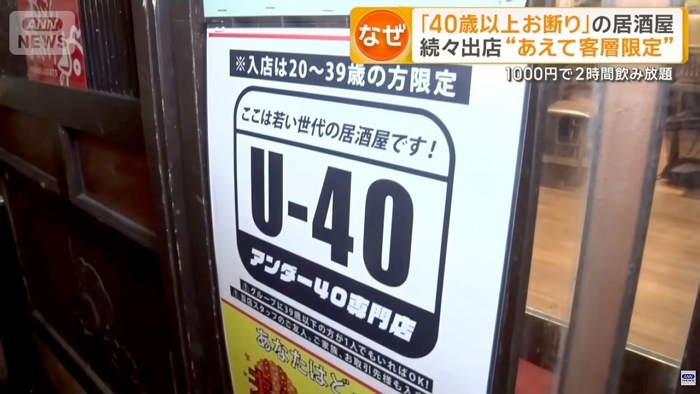

Photo: Washington Post video caption

His trash mostly consisted of a few chip bags, glass milk-bottle caps, fruit stickers, and broken glass. He obviously had to make lots of sacrifices to achieve this – he stopped buying any kind of packaged food including cheeses, only drank milk from recycled glass bottles, and gave up on buying new clothes or stuff for his home – no gadgets, furniture, or even mugs. He began carrying his own fork, spoon, plate, and a bowl everywhere he went, just to avoid plastic cutlery.

“I needed to change the way I lived, and I needed some parameters,” he told The Washington Post. “Everything apart from food scraps (which I’d compost), toothpaste and soap (which were too difficult to recover), and toilet paper, counted as trash or recycling. I collected my refuse – concert tickets, stickers, plastic tags, packaging, glass, you name it – and didn’t throw it away.”

“I had to get creative,” he added. “When a restaurant furnished a napkin-wrapped fork and knife, I asked the server to change them for cutlery without the napkin. I’d remember to say “No straw!” after asking for water and to make sure the veggie burger I ordered didn’t come with a wooden pick holding it together. I did what I had to do, and it was awkward.”

Photo: Washington Post video caption

But he did make a few exceptions. “I couldn’t always control other people’s behavior, so junk mail wouldn’t count as my own recycling. I wasn’t going to be a bore and instruct a dinner-party host on how to reduce trash. And if someone gave me a gift – a token offered from the heart – I accepted it.” He also separated his requirements of single-use materials at his lab, from his personal habits at home.

Although Karwat didn’t give up toilet paper initially, five months into the experiment he realised that he’d have to, in order to be truly trash-free. And for him, that was the biggest challenge – he admitted that it was unreasonable to give up at the beginning. But eventually managed to get over the ‘gross factor’.

“Deep-rooted in culture’s psyche is its obsessiveness with its sanitary ways, toilet paper, and paper products chief among them,” he wrote on his blog when he made the decision to stop using toilet paper. “The ecological impacts of our standards of sanitation? Hmm. And so a few months ago, I gave up toilet paper. That’s right. No ‘recycled’ toilet paper, no toilet paper whatsoever. I use a little water bottle, and… my… hand. And take it easy, I still use soap.”

“It works, and it feels much better than wiping your a** with a piece of paper.”

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Giving up on so many things also meant that Karwat’s social life took a beating. Bringing his own glass to parties to avoid using paper cups wasn’t cool, but in the end, he thought it was all worth it because he was able to prove that people could follow sustainable lifestyles if they choose to. And when he looks at the big picture, he doesn’t believe his life really changed all that much.

“In many ways, though, my life didn’t change much,” he wrote. “I had grown up in a humble setting in India, where I was accustomed to consuming as little as possible. I was a member of the People’s Food Co-op in Ann Arbor, where I bought my produce unpackaged. I didn’t even have to become a recluse. Rather, my quality of life improved. I learned to be more present in my choices, and I learned what is important to me, regardless of what others think.”

Karwat believes that if he could live a trash-free lifestyle, anyone can. And he says more people should give it a try, to be able to make a dent in America’s $52 billion trash industry that produces 250 million tons of trash every year. “We don’t have to go back in time to heed environmental boundaries,” he said. “We just have to be creative. What began as a one-year experiment ultimately lasted two-and-a-half years, the rest of my time in Ann Arbor.”

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

But Karwat says he doesn’t judge people who can’t follow in his footsteps. “Others don’t have the flexibility or means for this kind of activism,” he wrote. “Or they may simply have more immediate concerns. Consumption is so convenient that it is truly invisible and routine. I tried my best not to be sanctimonious to people less committed than I.”

Karwat himself has found it difficult to replicate his trash-free lifestyle since he moved from Ann Arbor to Washington. “Standing in my kitchen in Washington, I think about the waste I generate now, in a city that doesn’t have the same infrastructure as Ann Arbor has,” he said. “It has been more than six weeks since I moved here, but my one-and-a-half-gallon trash and recycling bins are both full already.”

“It’s time for me to go to the chute to send these materials to a landfill and a reprocessing facility. It’s not like I’m a profligate consumer today, but I can’t say it doesn’t hurt.”