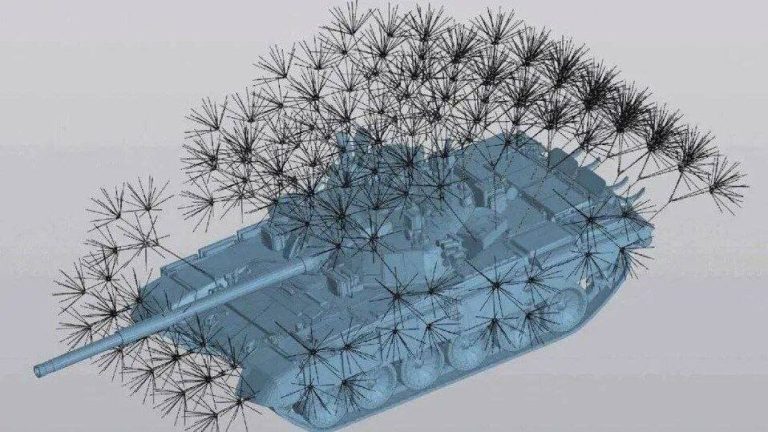

20 years ago, a couple of ecologists fighting for the conservation of Costa Rica’s tropical ecosystems convinced a large orange juice producer to donate part of their forestland to a national park in exchange for the right to dispose of massive amounts of orange peels on a degraded plot of land within that same park. No one had any idea what an impact that would have.

In 1997, Daniel Janzen and Winnie Hallwachs, a husband and wife team of ecologists working with the Área de Conservación Guanacaste national park, in Costa Rica, came up with a plan to save a piece of unspoiled, completely forested land from a big fruit juice company, by offering something very attractive in return. If the company, Del Oro, agreed to donate part of its forested land to the Área de Conservación Guanacaste, they would be allowed to deposit massive amounts of waste in the form of orange peels on a 3-hectare piece of degraded land within the national park, at no cost. Disposing of tons of leftover pulp and peels usually involved burning them or paying to have them dumped at a landfill, so the proposal was very attractive.

Photo: Princeton University

Del Oro dumped around 12,000 metric tons of sticky orange waste in the Área de Conservación Guanacaste, but a year after the contract was signed, TicoFruit, another juice company and rival of Del Oro challenged the deal in court, arguing that their competitor was “defiling a national park”. They ended up winning, and the deal between Del Oro and the national park fell through.

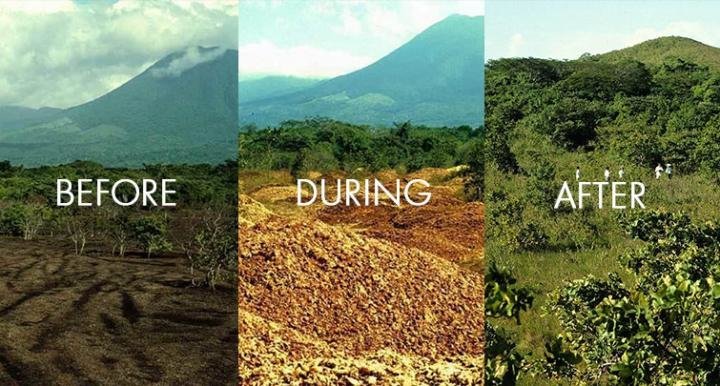

For the next 15 years, no one really monitored that 3-hectare piece of land that had been virtually covered with fruit waste. Then, in 2013, while discussing possible research avenues with Timothy Treuer, a scientist at Princeton University’s Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Daniel Janzen mentioned the orange peel story, and how the land had been visited by other researchers, but not properly evaluated, over the last one and a half decades. Intrigued by Janzen’s idea, Treuer decided to stop by that piece of degraded land that had been covered with fruit waste 15 years earlier. What he found shocked him and his team.

Photo: Princeton University/ZME Science

“It was so completely overgrown with trees and vines that I couldn’t even see the 7-foot-long sign with bright yellow lettering marking the site that was only a few feet from the road,” Timothy Treuer recently told Princeton University. “I knew we needed to come up with some really robust metrics to quantify exactly what was happening and to back up this eye-test, which was showing up at this place and realizing visually how stunning the difference was between fertilized and unfertilized areas.”

“The site was more impressive in person than I could’ve imagined,” added Jonathan Choi, who was a senior studying ecology and evolutionary biology at Princeton when he joined Treuer’s research team. “While I would walk over exposed rock and dead grass in the nearby fields, I’d have to climb through undergrowth and cut paths through walls of vines in the orange peel site itself.”

Photo: Princeton University

But this visual difference between the 3-hectare orange peel dump site and the surrounding degraded land was not enough to confirm that the fruit waste was responsible for the revival of plant life. Treuer and his team spent months picking up samples, analyzing and comparing them. They found “dramatic differences between the areas covered in orange peels and those that were not. The area fertilized by orange waste had richer soil, more tree biomass, greater tree-species richness and greater forest canopy closure.”

“This is one of the only instances I’ve ever heard of where you can have cost-negative carbon sequestration,” Treuer said. “It’s not just a win-win between the company and the local park — it’s a win for everyone.”

Photo: Princeton University

The effect that the orange peels had on the land are probably not that surprising to people familiar with composting, but what is downright shocking is that a judge actually called this particular example “defiling” of a national park and stopped it from going forward. Now that Timothy Treuer’s study has received worldwide attention, this type of defiling is being seriously considered as a way of bringing tropical forests back to life.

“Plenty of environmental problems are produced by companies, which, to be fair, are simply producing the things people need or want,” said David Wilcox, co-author of the Princeton study. “But an awful lot of those problems can be alleviated if the private sector and the environmental community work together. I’m confident we’ll find many more opportunities to use the ‘leftovers’ from industrial food production to bring back tropical forests. That’s recycling at its best.”

Photo: Princeton University

via ZME Science